The air of commerce hung thickly over the lowlands along the upper Missouri River, nestled between buttes and fields of sweetgrass.

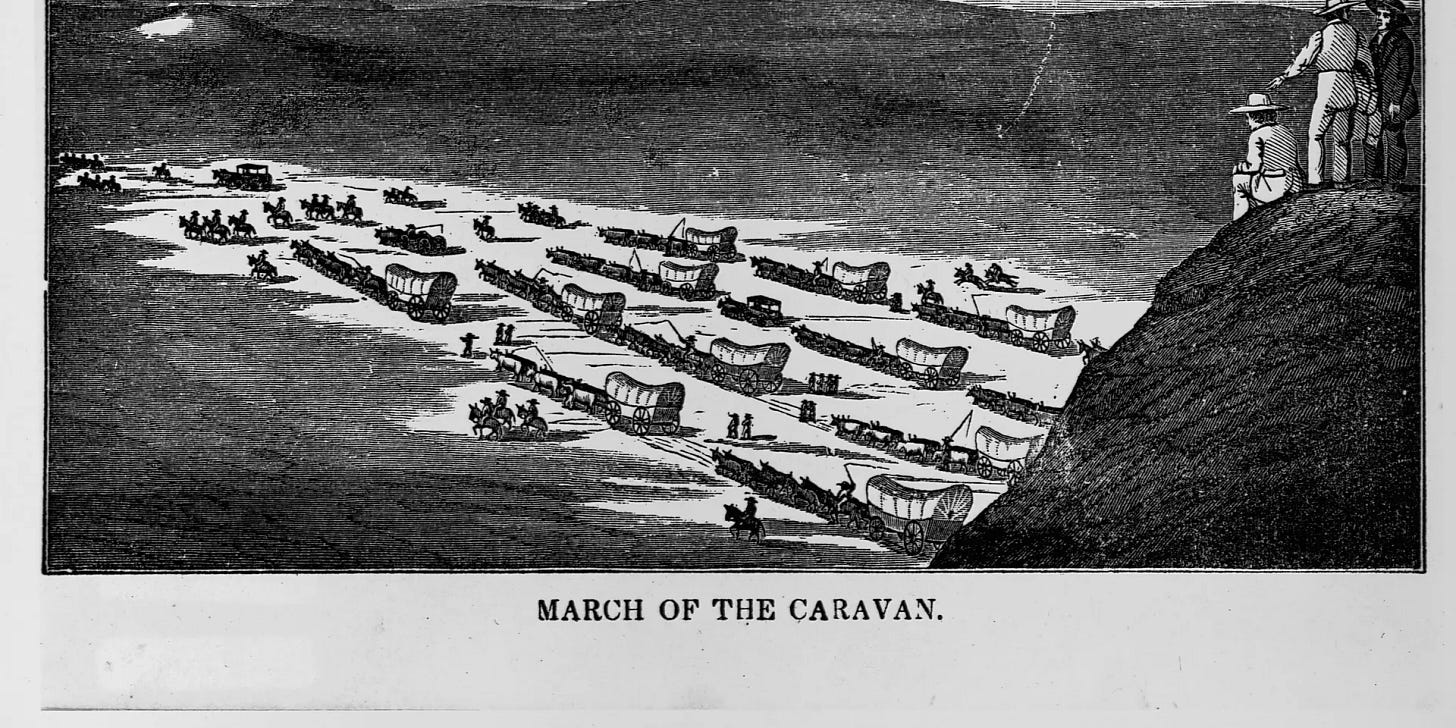

As the Comancheros roamed the southern plains, engaging and maneuvering eastern plainsmen, traders, and wagon trains, the northern territories rarely bore witness to a lily-livered Crow, Cheyenne, or Sioux. It is safe to say the mere sight of a distant caravan ruffled every Native's feathers, but not solely theirs.

One particularly striking event in May 1817 illustrates the tensions of the era: Auguste P. Chouteau and Julius De Munn, leading a group of hunters and trappers, were abruptly seized by Spanish troops along the Arkansas River, all on account of mistaken boundaries. Taken to Santa Fe, they were confined in irons for forty-eight days. A change in governance spared them further punishment; the new governor ordered their release, albeit on the poorest nags available, and sent them back to St. Louis. Their confiscated goods resulted in a devastating blow, losing nearly $30,000, erasing two years of trade efforts. Although this incident unfolded years earlier in the south, its aftermath—ripples of discontent and a pervasive struggle for dominion—continued to resonate in the valleys and hills of northern Montana, influencing the region's dynamics long afterward.

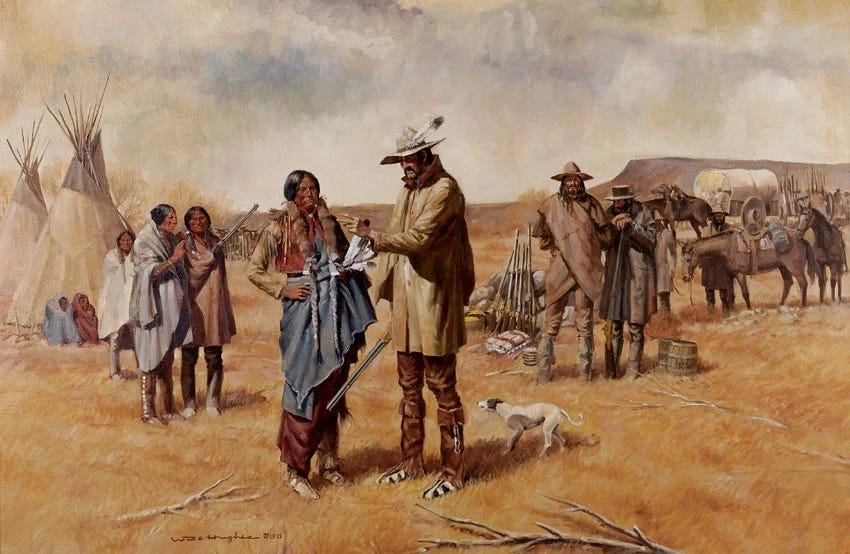

The bond between all parties, regardless of their differing appearances—the reddened, painted faces of the Natives against the pink, sun-tanned complexion of the traders—was the epitome of the era: Fur.

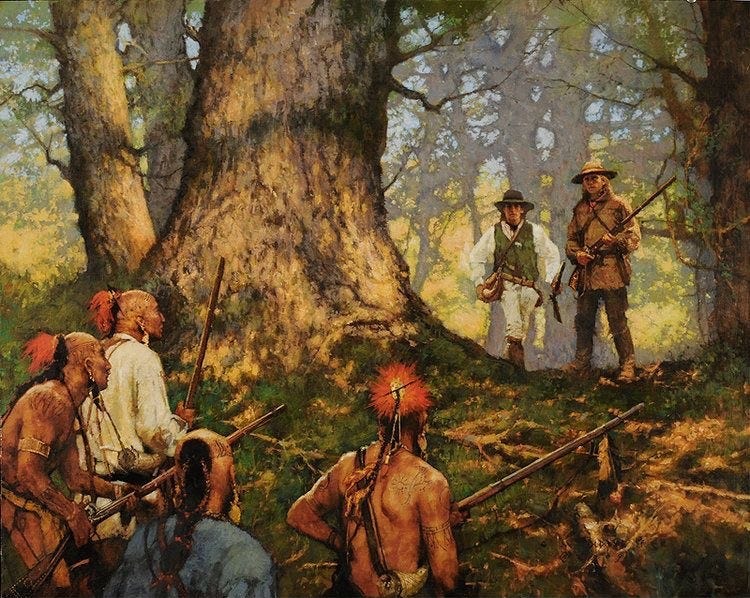

As much of a shared enterprise as it was, one year of trading with the Arikara or Blackfoot may differ from the following season, as alliances could dissolve into enmities overnight. All tribes had their ancestral foes and allies despite their distance, as if they were city-states only sparring hunting grounds, slaves, or women. Furthermore, neither the Sioux nor the Crow were fond of each other on account of previous raids, horse-thieving, and border wars.

Therefore, what was once a welcoming parade for the trapper—war chiefs and children alike dancing upon his arrival—became as risky as a coin toss.

The Scots-Irishmen, the French, and the Spaniards did not think too profoundly of such fickleness; they only detested it. This venture meant one's livelihood. However, changes in accords were not just whimsical decisions by the Natives, regardless of the brutal and cruel ways they severed ties.

Amidst the vast expanse of the plains, emigrants might grapple with the desolation yet remain oblivious to the spectacle of the Native in his spiritual, animistic essence. To the typical frontiersman, offering a parcel of meat to a grizzly in respect of its sacrifice seemed nonsensical, an unnecessary deference to the mere inevitability of nature's cycle. For the Native, such acts were customary, rooted in a worldview where every element of existence was interconnected. The stars that adorned the night sky, the horizon where earth and sky seemed to embrace, the ground that steadied one's stance—all were part of a cohesive whole that included humanity.

Unlike many settlers who drew a firm line between the divine and the earthly, equating the love of God with dominion over nature, the natives saw no such division. This connection, where man and nature were not just adjacent but entwined, aligns with what French anthropologist Lucien Lévy-Bruhl termed ‘participation mystique’—a concept not limited to any single group but prevalent among various indigenous peoples living non-agrarian ways. For the Crow, in particular, to engage with nature was to engage with a part of oneself, a sacred communion where every breeze and rustling leaf held a spirit as vital as their own.

Through the lens of God-fearing emigrants, the legends of battle-scarred warriors left a notch in the imagination of many.

To the settlers, the Natives seemed bereft of a familiar God.

The Cheyenne regard Ma'heo'o, or the Wise One Above, as a central figure and often consider him a creator or supreme being within their polytheistic belief system. Among the many archetypes in their mythology are Sweet Medicine, the bearer of the Four Sacred Arrows, the lone warrior Motzeyouf, and Burnt Face, whose story of trials and resilience parallels the biblical narrative of Job. While the Cheyenne were similar to the Crow and fond of the sharing of ponderance on their creator, the Sioux were notably entrenched in rituals of self-sacrifice, inflicting slashes upon themselves or other self-inflicted wounds, asserting themselves as warriors under the eye of one all-pervasive god, Wakan Tanka, or the Great Mystery. Much is to be said, studied, and taught about the sun dances, vision quests, or the various forms of prayer performed before a battle cry. Most, if not all, tribes shared similar traditions, some more nomadic than others, others more skilled in horsemanship than their huntsman brethren.

One tribe many a settler wrote of, witnessed in action and was lucky enough to have kept his hide from was the Comanche—loosely termed “buffalo eaters.” “Comanche” originates from a Ute term that roughly translates to “those who are always ready to fight.” They certainly lived up to their name.

The Comanche, once a part of the Shoshone, drove southward. They moved in dispersed waves, showcasing unparalleled horsemanship and brute force with every gallop. Renowned as the epitome of nomadism and domination, they monopolized trade routes and rekindled yesterday's vendettas for tomorrow, continuing the perpetual cycle of revenge and retaliation. Among their most bitter rivals were the Apache, whom the Comanche relentlessly pursued, ultimately expelling them from Texas.

The fear that gripped a person caught unarmed in the vast prairie is hard to overstate, confronted with the immovable blockade of horseback braves, all deadpanned and silent, carrying a semblance of omniscience—reigning all-supreme judgment—as if they were the gods of the plains. As Herman Lehmann recounted in his autobiography, Nine Years Among the Indians:

“We moved toward the Comanches, camped within three miles of their village, and raised a flag of truce. The Comanches sent out a warrior, who galloped around us at a safe distance, waving a black shield in the air. This meant fight, death to the vanquished. Had the Apaches sent a man in return with a red shield, it would have meant we accepted the challenge and were ready to fight, but we raised a white flag, which meant peace.” (Lehmann, 1927, p. 44).

With every ounce of territory known as Comancheria, stretching from present-day New Mexico to Oklahoma, Colorado, and close to Nebraska, the Comanche were titled “Lord of the Plains,” and they had much to show for, grudgingly sharing land with the Kiowa and others. Peace with the Comanche was a shot in the dark, only in the face of necessity, their wariness as vast as the plains they ruled.

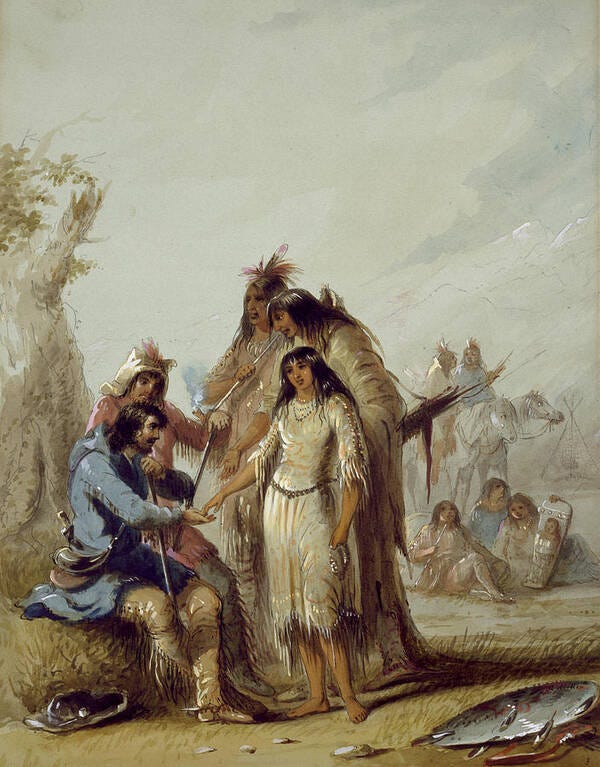

Away from grand conflicts and prowess among the plains, a trader often found himself sitting cross-legged around a fire, with either partners or enemies of the tribe a mile over, passing pipe and stories, language and gesture; it was worth his time to become acquainted with his business allies, lest he lose his topknot. One quote by Alfred Jacob Miller sums up quite well the challenges faced by tradesmen when maneuvering the Indians:

“The Trappers experience much difficulty in acquiring a knowledge of the Indian tongue, and as if the language was not embarrassing enough, its pronunciation is still more puzzling—the sound proceeding from the throat. It requires them to sojourn for years amongst the tribes to acquire anything like proficiency, and in the absence of this, they resort to signs, the meaning of which they learn readily, and thus hold animated conversations.” (Alfred Jacob Miller, The West of Alfred Jacob Miller, 1837).

Within the complexities of trapping life and native tradition, more personal commerce often unfolded—a necessity born from the desolate stretch of the frontier. Many a trapper, soaked, wrung out, dried, and tanned under the sun, wound up bound in marriage to a woman of the tribes. These were no fairytale unions but pragmatic partnerships etched out of the harsh realities of opportunity among scarcity. For him, a Native wife was not only a companion but a bridge to her people, a crucial link that could mean the difference between prosperity and peril in the erratic nature of tribal relations. Still today, marriage involving non-tribal members to tribal members is something to be considered with awareness of tribal laws and customs.

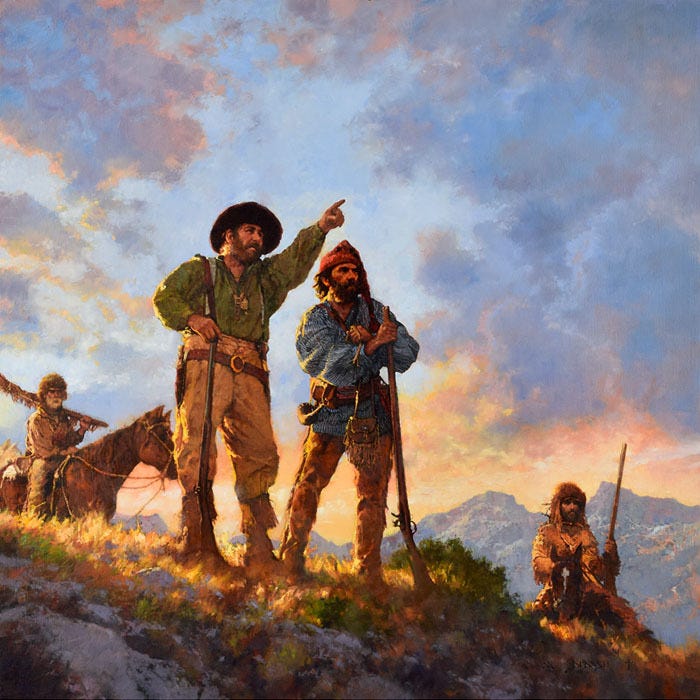

When reflecting on the Old West and the Fur Trade era, we should not strive to romanticize such periods in a way that undermines the grit that made people who they were: the irrefutable fact of determination that sprouted from the soil to the ends of the frontiersman's fingertips. It was not only he who traveled the vast expanse in search of unknown treasure—or better, hidden opportunity—but any man who sought out the land for his taking, with his family in tow, adorned in the pelts of critters or otherwise. These men, often exemplifying rugged individualism, embodied a philosophy rare to grasp in modernity. Each frontiersman carried a shadow of struggle against the relentless forces of nature.

It is easy to say they were isolationists, yet it was not due to a lack of companions. A horse and a rifle suited him fine for some time. During the nights spent in the nook of a tribe, man created many memories and tales to pass on so that he did not merely keep his pride for his people. Doing so birthed coalitions grounded more in practical relations than trust, laying the foundation for further exploration of this land we now know and cherish.