Exploring American Identity Through a Jungian Perspective

A personal observation of the hidden layers of the unconscious shaping America’s digital landscape and national identity

While America is known for its amalgamation of peoples, anonymous figureheads and creators within the virtual realm reveal their shadows and, unashamed in plain view, yelp out from the dark about their desires for their country and people while clinging to their armchairs. Platform users are expressing far more than concerns over current events. This essay, however, focuses on those expressions, highlighting how cultural shifts influence historical development through Jungian concepts like the 'shadow,' the 'collective unconscious,' and 'archetypal patterns.'

Ideally, such virtual spaces would facilitate unity and connection. However, they have magnified characteristics of individuals, such as egoism, that do not pertain to any specific 'root' or people but to a collective unconscious. Studying psychoanalyst Carl Jung's theories on the collective unconscious can better help one understand this circumstance. As Jung explains in his essay, The Role Of The Unconscious, “The unconscious contains everything psychic that has not reached the threshold of consciousness,” highlighting the vast repository of forgotten and repressed elements that shape our behaviors and identities. He further states, “We have already taken cognizance of repressions as contents of the unconscious, and to these, we must add everything that we have forgotten,” emphasizing the depth and breadth of the unconscious mind. (C. G. Jung, The Role of The Unconscious, Collected Works; Civilization in Transition, Vol. 10., (2nd ed.), p. 8, §8).

Jung’s exploration of these psychic repressions came at a time when all of Europe was reeling from the devastations of World War I, and individuals were attempting to cope with the psychological aftermath.

Further in his essay, Jung differentiates between the personal unconscious—material related to an individual's experiences—and the collective unconscious. The personal unconscious consists of elements derived from an individual’s life experiences, such as memories, thoughts, and emotions that have been repressed or forgotten. In contrast, the collective unconscious is a deeper, shared level that contains elements not personally acquired but universally and culturally inherited. As Jung described, it is a repository of archetypes and symbols common across humanity, or “everything that we have forgotten.”

In the digital domain, where most seem to live and act out their lives, this eruption of less conscious details exposes the undercurrent of America's collective psyche, putting historically embedded tensions and archetypes of the nation's identity on full display.

It is easier to dub the medium we use today a neon labyrinth, each door opening to awesome yet dangerous invitations while expanding consciousness. For the youth, navigating this maze has taken its toll. One cannot experience life when memories are stored in a 'cloud.' However, considering the extensive coverage of this subject in previous essays, it is not to be written here.

Children have their excuses, as they are being raised in a prolonged state of infancy in today's world. They can blame their upbringing up to a point, which is a natural response. However, it becomes more concerning when adults, fully cognizant of their actions, still fail to recognize how they impact the macrocosm of history and the nation itself.

For the American, submerging himself in the collective rally could be seen as escapism and a denial of his personal reality. Behind the veil of anonymity, one allows his shadow to overtake him, compromising his values. The current American has become the microcosm of the ongoing conflict between the conscious ideals and the unconscious drives that are part of the national psyche.

Initially, Americans were more individualistic than the Europeans, pioneering freedom and the idea that each person should 'make his own way.' This attitude has not only been admired but has also remained both an aspiration and envy for neighboring lands, where such bravado is hardly attainable.

Jung stated in his essay Mind and Earth:

“Thus, the American presents a strange picture: a European with Negro behavior and an Indian soul.” (C. G. Jung, Mind and Earth, Collected Works; Civilization in Transition, Vol. 10., (2nd ed.), p. 49, §103).

Jung made this observation in the early twentieth century; however, the claim still holds ground today. The American must accept himself for what he is. As much as the impoverished man dwelling in the hills of Appalachia wishes to return to his distant European roots, he cannot recreate what has been bred out, dismissed, and retired. For the American, pursuing a futile attempt to embrace a simulacrum of European culture or a desire for ethnonationalism only deepens the divide within one's identity, amplifying feelings of disconnection and alienation from his present reality.

Ironically, it is increasingly apparent that even prideful Europe has swung in the opposite direction regarding identity, gung-ho in its acceptance of various cultures and faiths, including Islam. Perhaps they have gone to unnecessary lengths to amend their heinous sins.

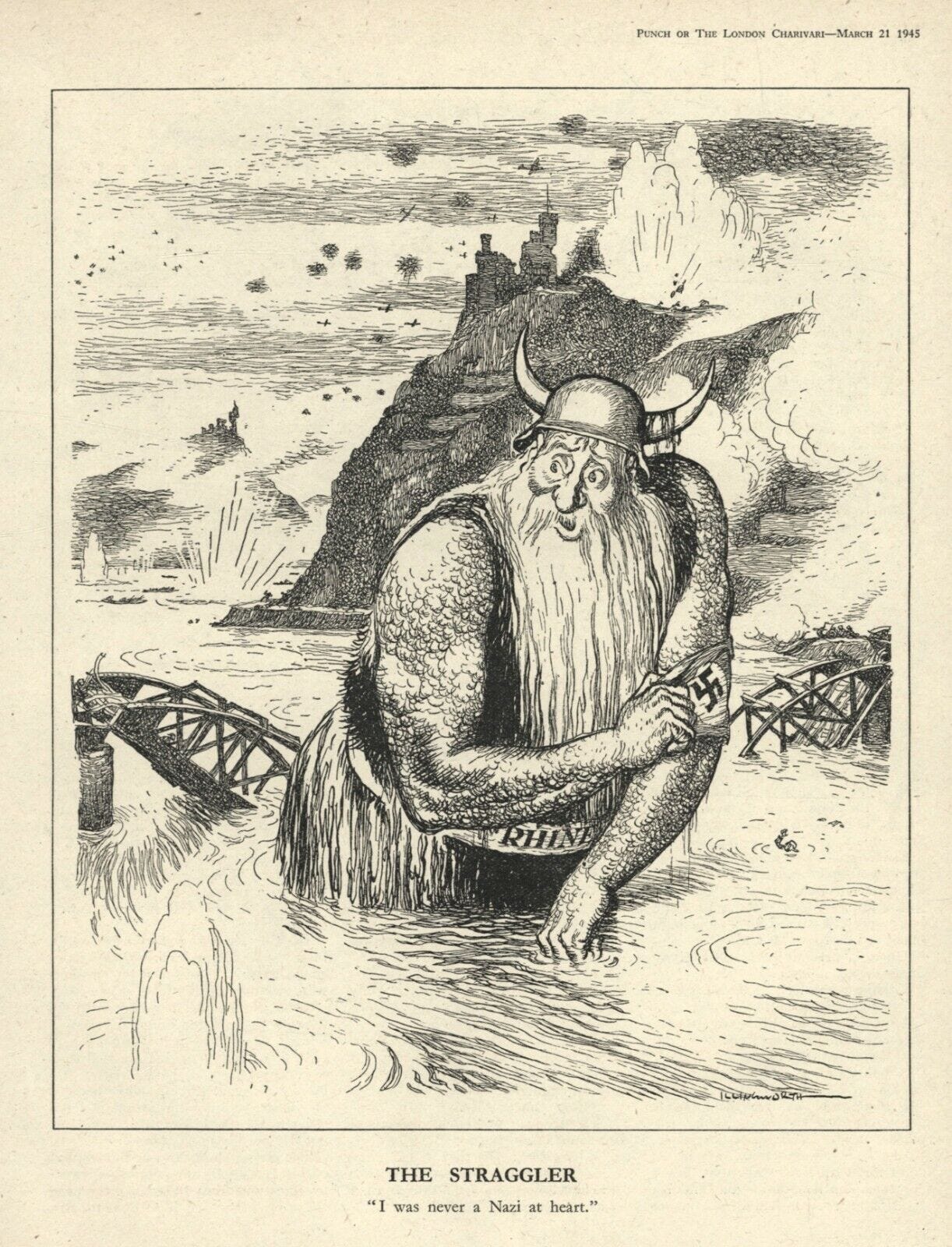

In a European context, ethnic identities sprouted amid turmoil and desperation. In Germany, the romanticization of pre-Christian, Teutonic, and Norse mythologies during the Nazi era was a form of 'ethnic identity' resurgence, which ignited a foul arrogance within the people, and the fallout is evident. This reactivation sought to unify the populace by appealing to a glorified, mythical past that was distinctively Germanic.

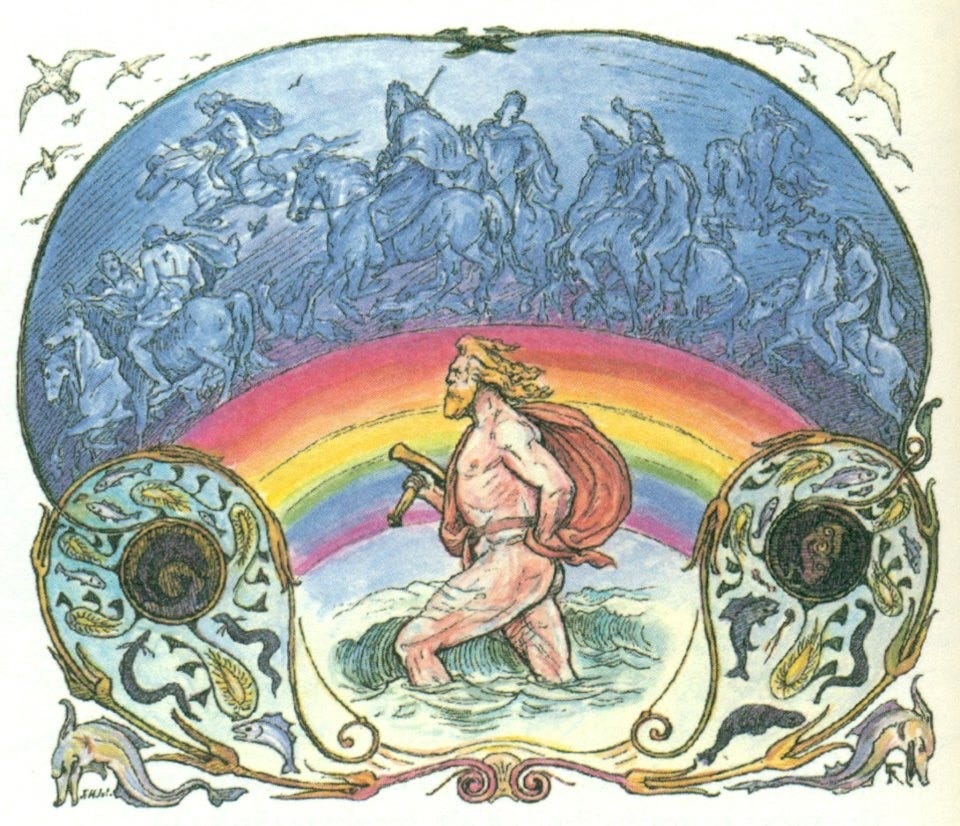

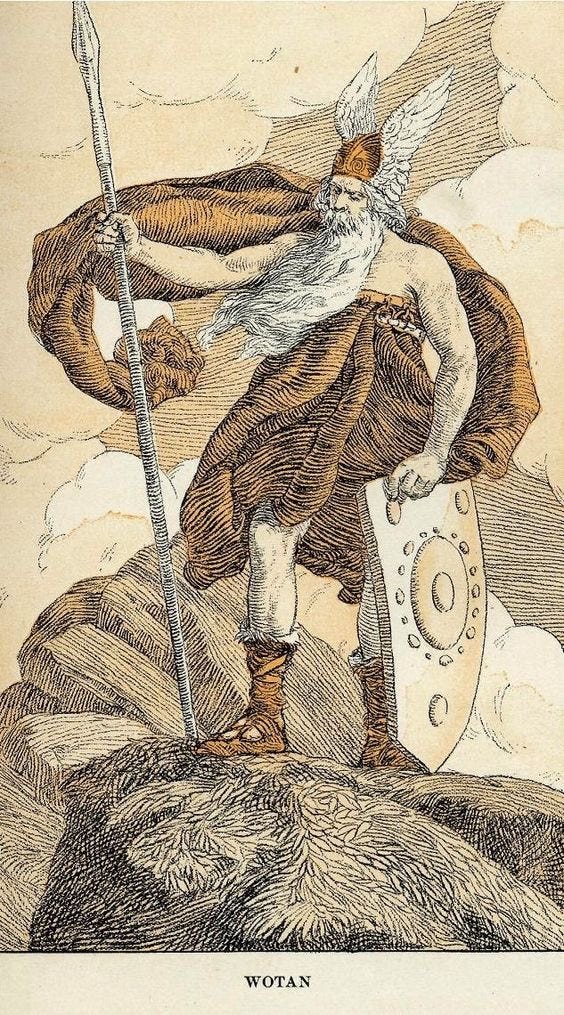

The quest into antiquity and the depths of the unconscious—to uncover and engage with the archetypes of one’s European heritage—is noticeable in the online realm. Such a dive signifies an unfiltered and naked search for Wotan, an archetype Jung conceptualized as a god of fury, frenzy, and destruction.

The same individuals, while striving for a connection to what they perceive as their roots, inadvertently channel the unconscious archetypes that Carl Jung describes. This intense and often unconscious re-engagement with archaic figures like Wotan symbolizes a more profound psychological process. Jung claims these archetypes stem from the collective unconscious and influence behaviors and cultural expressions, manifesting in ways individuals may not fully understand or control.

As Jung explains in his essay, Wotan:

“Archetypes are like riverbeds which dry up when the water deserts them, but which it can find again at any time. An archetype is like an old watercourse along which the water of life has flowed for centuries, digging a deep channel for itself. The longer it has flowed in this channel, the more likely it is that, sooner or later, the water will return to its old bed.” (C. G. Jung, Wotan, Collected Works; Civilization in Transition, Vol. 10., (2nd ed.), p. 189, §395).

However, what does the 'old bed' look like for America? The place in which many found themselves shaken into consciousness from their acclaimed slumber, what may it resemble? The earliest pioneers, settlers, gold panners, and farmers were not taken hostage by a famous Ergreifer—a term Jung dubbed the archetype Wotan during Hitler's reign—possessed by a collective force. This idea seems doubtful as Americans were and remained, initially and to the best of their ability, individuals. These bright-eyed argonauts became conquerors of a foreign land quickly and without hesitation. Yet, neither a collar-gripping Ergreifer nor the pioneer archetype fully and persistently captivates the essence of Americanism.

In Jung's essay Mind and Earth, he mentions that “certain Australian primitives assert that one cannot conquer foreign soil, because in it dwell strange ancestor-spirits who reincarnate themselves in the newborn.” In his explanation, Jung concludes that a “foreign land assimilates its conqueror” and that, while North Americans held fast to their Puritanism, they “could not prevent the souls of their Indian foes from becoming theirs.” This integration had been growing, sprouting from the novel concept of such an enterprise that would uproot the European from who he had been until that point.

Jung did not make such statements without providing evidence he observed during his clinical profession and international journeys. Near the end of his essay, Mind and Earth, he makes a fair point:

“. . . But as the great majority of dreams, especially those in the early stages of analysis, are superficial, it was only in the course of very thorough and deep analyses that I came upon symbols relating to the Indian. The progressive tendency of the unconscious, as expressed, for instance, in the hero-motif, chooses the Indian as its symbol, just as certain coins of the Union bear an Indian head. This is a tribute to the once-hated Indian, but it also testifies to the fact that the American hero-motif chooses the Indian as an ideal figure.” (C. G. Jung, Mind and Earth, Collected Works; Civilization in Transition, Vol. 10., (2nd ed.), p. 47, §99).

On fresh soil, the immigrant became 'Indianized' more than 'Americanized,' presenting a rift between his conscious level of culture and the deep unconscious rumbling of primitivism. It would seem plausible that this has changed over two hundred-plus years; however, the nation remains as tribalistic as it was during the first Thanksgiving.

While Europeans have, in the past, maintained a strong continuity with their historical and cultural roots—allowing for a unification of their collective unconscious into their modern identities—Americans are finding themselves bereft on this plane of self, akin to a rebellious teenager seeking his purpose among silver-tongued charlatans.

It seems to be worse for the youth who lack knowledge of history, which will only worsen if Americans do not reckon with the peculiarity of their identity.

As difficult as it may be due to the roots of this nation, we must strive to focus on the individual, individually—away from the grasp of any collective, virtual or otherwise—and conclude that shared values ought to precede egoism and nostalgia. Otherwise, man is sure to fall on the sword of his shadow, caught up in the blunder that is ignorance and power. The American is war-like when left unchecked by his consciousness.