The New Right and Its Reckoning

Old values, new platforms, and the identity crisis in between.

The political Right now faces a growing dissonance between its inherited values and the nature of its actions, particularly in how those values are expressed and perceived in the digital sphere. In a fully virtualized reality, where generational succession is underway, and the young are usurping the techniques of American politics, the consequences of a disintegrated symbolic structure, combined with performative expression, are imminent.

There is something striking in the way that what the Right has held sacred from its founding—conservation, personal sovereignty, moral accountability, and resistance to collective ideology—has been more or less swept under the rug by virtualism. Undoubtedly, the classic conservative still exists: the “boomer” who owned property, a home, and a family built from the land. Therein lay his purpose for conservation, the perpetual upward aim of what was righteous to strive toward. In some ways, this was individuality in action. The soil connoted structure, the skyward ascent, the ‘coming together’ of parts to assemble what was symbolically essential for man to continue his work. What the older conservative embodied—unconsciously—was something closer to Jung's notion of individuation: the process by which a person becomes whole through the integration of duty, labor, meaning, and the confrontation with moral responsibility. His life was not symbolic in an abstract sense. It was made significant through sacrifice, stewardship, and the forging of a self concerning land, family, and faith. The outer structure mirrored the inner one. He may not have spoken of individuation, but his rootedness provided a scaffold. Granted, one cannot fully understand the individual psyche of another; however, on the scale of action versus idleness, it is usually the former that leads to maturation in most psychological states.

“The aim of individuation is nothing less than to divest the self of the false wrappings of the persona on the one hand, and of the suggestive power of primordial images on the other.”

(Jung, The Function of the Unconscious, CW 7, par. 269.).

To act is to be invested in one's reality and, therefore, to conserve what matters. It is hardly about the present so much as the future; the traditional conservative understood this principle. While critiques of that generation may be valid, one can say with fairness that acting was not their weakness.

As explored in a previous essay, the ‘Indian soul’ of America—the psychological orientation toward instinct, action, and ruthlessness that Jung identified as primitive yet distinctly American—is equally visible in the old conservative and the modern, hyper-online partisan who leaps on any cause that flatters his agenda. Both exhibit the pattern of “acting without thinking,” yet in different forms.

Today, the scaffold that once anchored the classic conservative is absent. Without describing the myriad economic blockades that prevent the youth from progressing as quickly in life as they desire, it is generally assumed that the inertia that the Right faces is something they must contend with in policy, duty, and action. For those who voted for such a shift on the economic front, it would be unwise to hold their breath. As it stands, stagnation appears to be the party's most natural trajectory. The values passed down have become slogans, not convictions—if they ever were convictions to begin with. The influence of liberalism has mostly severed the transmission of beliefs and ideals of preservation and integrity. With this, the idea of conservation is smoldering, and more importantly, the question of “what is there to conserve?” remains.

The Projection of the Right

It would be unjust to assume that all who identify with the political Right are actively immersed in the hyper-online world, the digital Times Square, where trends and ideological motifs whiz by. Many still live in motion, oblivious to the flood of performative allegiance online. Those who remain uninvolved are quietly fading, and the legacy media through which they once received their news and worldview is withering alongside them.

The results of the last election demonstrate that the impact of virtual engagement among parties is significant; the influence of enthusiastic millennials and younger voters is palpable. It goes to show that such a conglomerate utilizing the medium as it does deserves a precise critique of its methods. In fact, one of the highest virtues of the Right remains its ability to “reel itself in”—to uphold a standard, to self-correct. If it is to persist, that virtue must apply to both physical action and virtual projection. Digital expression will continue to grow, and both the Left and the Right will manipulate their values through it, often without realizing it. As a result, the Right shapes its identity through what it projects publicly, and the digital atmosphere it creates allows others to infer its direction. It is up to those within its ranks to analyze its impact.

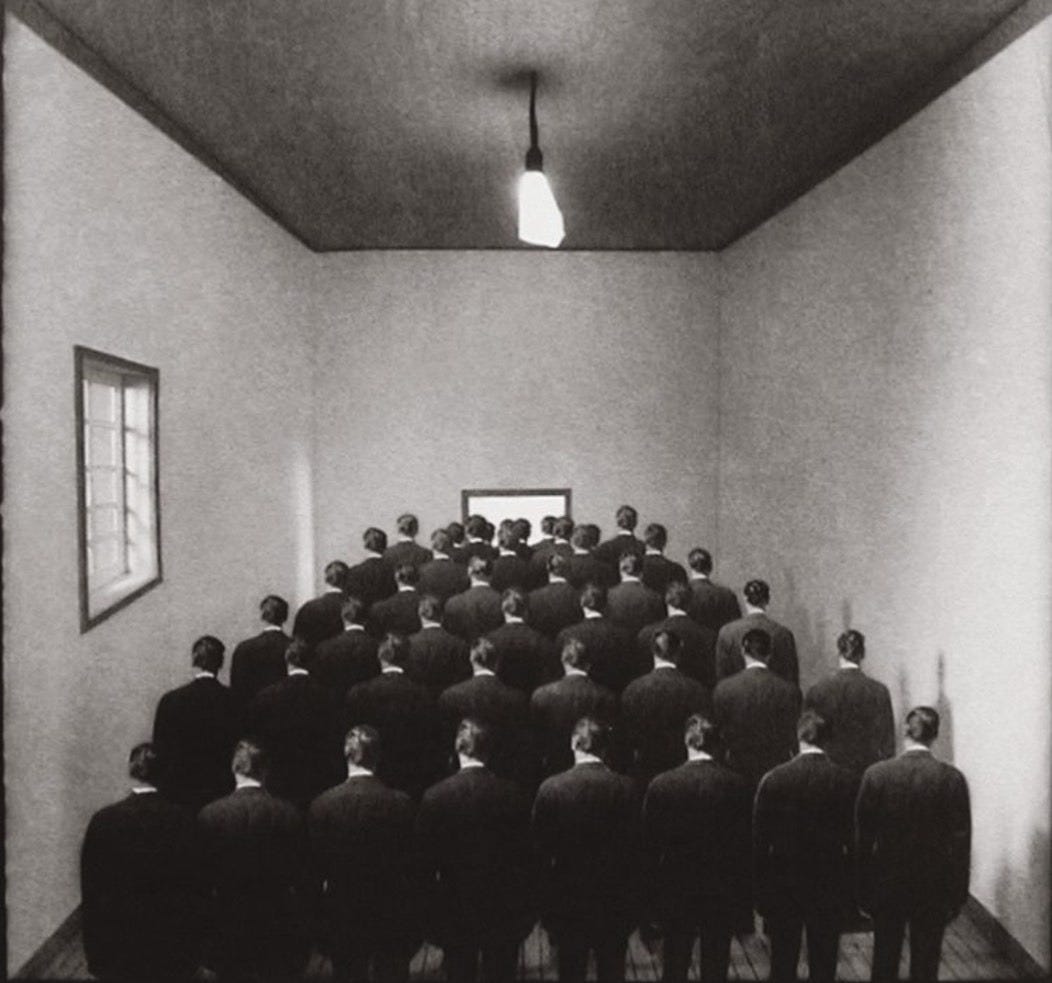

What now circulates most visibly from the Right in digital spaces is not a coherent moral vision but an aesthetic. A previous essay examined the methods by which most individuals—anonymous or not—tend to communicate their intentions for the party; all are primarily a form of reaction rather than acting itself. These expressions do not emerge from reflection or inner conviction but from alignment. They are tribal signals, designed less to persuade than to affirm in-group identity. The result is a performance of individualism, not the thing itself—identity as digital theater. For a generation with nothing underneath them, so to speak, with no grounding from conservative parents nor from the institutions that are now unstable and corrupt, this outcome may be understandable, even inevitable. Still, understanding does not equal justification. Expression alone does not confer depth. Rebellion without symbolic creation is merely noise. In Jungian terms, individuation is not just “standing apart” but giving something back, transforming inner struggle into value. Without this creative dimension, the modern persona risks becoming a hollow performance, mistaking visibility for virtue.

“The individuant has no a priori claim to any kind of esteem. He has to be content with whatever esteem flows to him from outside by virtue of the values he creates. Not only has society a right, it also has a duty to condemn the individuant if he fails to create equivalent values.”

(Jung, Adaptation, Individuation, Collectivity, CW 18, pars. 1095f.)

As Jung reminds us, individuation earns its esteem not by being different but by creating values others recognize as meaningful. This creation was not always intellectual or metaphysical in past generations, at least not in the European sense, but it was tangible. While the American psyche lacked the symbolic and philosophical richness of the Old World, it nonetheless embodied a grounded valence. Such was a form of meaning made real, not abstractly theorized. It may not have reached the heights of aristocratic reflection, but it met Jung's standard in another way: it contributed something durable.

The New Right's Individuality, or Lack Thereof

While the conservative party has long heralded individualism, it has never clearly grasped the concept, either historically or symbolically, or valued it as intensely as the responsibility one owes to family and community. Americans, across political lines, seem not to comprehend the European concept of aristocracy and thus lack a framework for identifying what is “best” and, therefore, what the party's best and most morally cultivated expression could be. Instead, the “common man” is worshipped, often regardless of his actions. Of course, America's founders did not build the nation on aristocratic principles but did not entirely reject its influence either. While the Constitution prohibits the government from bestowing a "Title of Nobility," the Founding Fathers were explicit in their preference for who was fit to govern beyond simply the People. At times, one can question whether those in power truly consider the authority of the People when making decisions.

America remains the youthful form of an old mold. The brazen pragmatism of the new frontier once served its expansion. However, over time, Americans have hardened this into a worldview where nobility feels foreign, and the public has lost sight of its standard. As for the “common man,” what began as a democratic virtue gradually solidified into a cultural ideal—one that resists hierarchy, exceptionality, and inward refinement. This populist ethos, while often defended in the name of liberty, quietly disincentivizes individuation. The common man is celebrated as he is, not for who he might become. If he resents the system under which he works or outsources blame to minorities and conspiracy, he is still granted the mantle of authenticity. However, the inference of “common” flattens the conditions that allow individuality and exceptionality to emerge. The man becomes symbolic only in his reaction, not in his reflection.

In this sense, American conservatism drifts dangerously close to a contradiction: it praises individual freedom while flattening the symbolic space in which the individual might form. Without some vision of the best, the common becomes a ceiling, not a beginning.

Granted, one might argue that the common represents shared values, faith, and national purpose, but this is not always true. The assumption that “he who looks like me must hold the same convictions” has not applied to America since its founding. Regardless, the intertwined existence of social media and reality makes such an idea absurd. A glance into the faux-Right corners of the internet would likely make even archaic ethnonationalists recoil, for online, appearance is meaningless; everything is masked by anonymity. In that belongs a type of cowardice. However, the problem is deeper than misrecognition. It is not merely a question of who belongs but of what defines the party at its best. That, as ever, comes down to duty, honor, and dignity—not alignment or reaction.

Yearning For Something More

For millennials and younger generations, the desire to return to what was lost—or to rekindle the fire that once burned in the belly of early America—remains strong. It is well on that path if the party seeks only a collective psychological regression. Such a trajectory will suffice if its leaders are content to rejoice under their mother's authority. Only Europe will not do the bidding this time. Those whose counsel America once rejected—out of pride or rebellion—will look on in pity or quiet laughter at the sight of our infantile conniption.

Yet, the fact that young people desire something more, with meaning, a compass, and depth, is a sign of potential. The idea of “something more” does not, and should not, equate to regression. What ultimately defines its trajectory is the mode of communication, the language used to convey the idea, and the actions surrounding the ambition. Outward expression shapes inward intent. Given that this longing remains conscious and self-disciplined, it may mark a natural path to maturity and individuation.

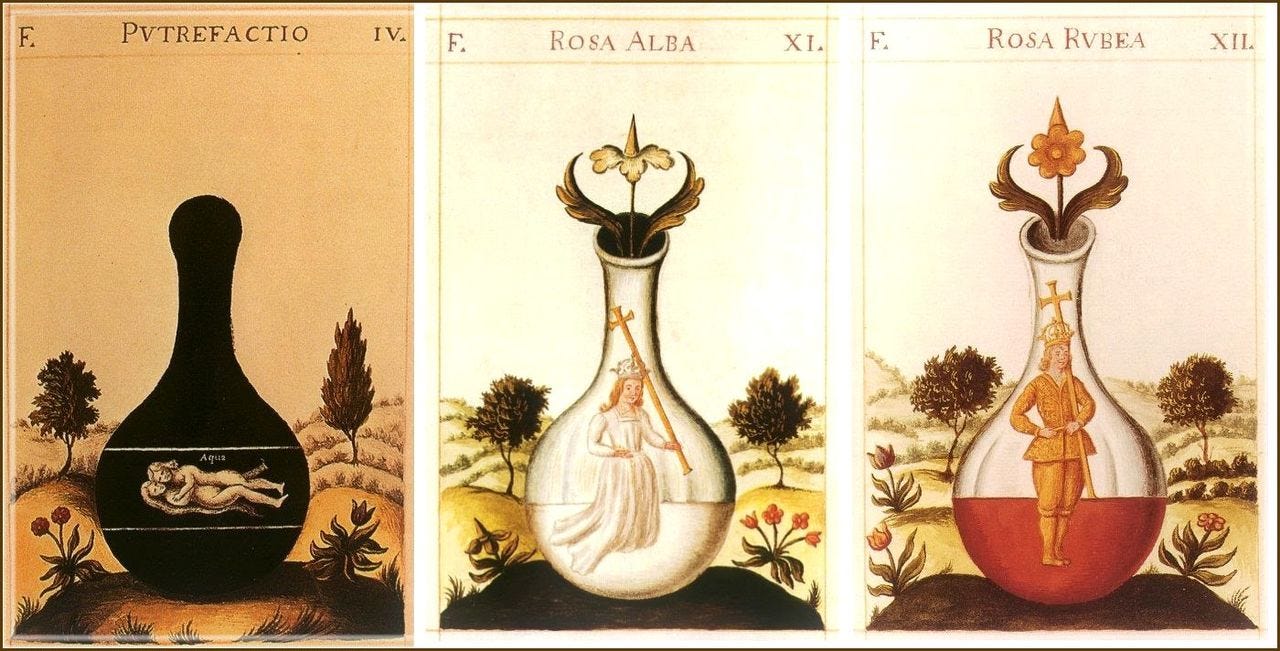

In a Jungian sense, the political Right is apt to face its Shadow. More importantly, it is reaching the necessary period of Nigredo: the death of a prior structure that no longer adequately expresses the truth of the psyche or, in this case, the essence of the party. It is a death before rebirth, an essential path to understanding what one projects onto others, and a stage of profound introspection on the journey to the Albedo, the illumination or spiritualization that follows. For individuals, such confrontations often arise around midlife; for America, still in its psychic youth, that confrontation may be imminent. As for the Shadow itself, the Right has long embodied a restrained, deferential posture—what might be called the soft-spoken ethos of Protestantism. The Shadow holds what is opposite or unclaimed in our conscious identity. To that end, it is reasonable to assume that the party, or even the country as a whole, harbors a Shadow full of traits once rejected. After years of suppression, outbursts are inevitable. In the virtual sphere, it is becoming evident that one's Shadow has free reign in ways previously impossible. This emergence does not equate to the individual acknowledging it, let alone integrating it. Still, it is a telltale sign of collective confrontation on a cultural scale.

The same dynamic, though in a different form, can be observed on the Left, perhaps even more so in recent years. Where the Right represses and may erupt, the Left externalizes almost constantly through compulsive virtue signaling, performative morality, and a denial of individualism. Projection runs rampant, not as a buried instinct but as a mode of expression. The Left does not face its Shadow—it wears it openly, unconsciously, and without reflection. There is no coherent self to confront—only a collective swirl of unexamined drives, chaotic and unorganized, masked as progress. Therefore, little is left to investigate, as everything is already displayed.

What Comes After

What is dubbed the ‘new’ Right should not be reduced to its loudest actors in the virtual arena; quite the opposite. The most visible expressions of right-wing energy may be the least representative of any coherent, enduring ideological vision. It is not a renewal but a reflex: a response to years of disillusionment, fragmentation, and symbolic erosion. The nihilistic “black pill” has taken root across both ends of the spectrum, but it metastasizes uniquely on the Right, where the longing for meaning has collided with the collapse of form. It is what remains when the symbolic order decays, but no inner transformation occurs. What the Right has long yearned for is a type of personality to emerge from its ashes after years of repression and tail-whipping under the Obama administration. What the Right got was Trump. Though he triumphed again, perhaps predictably, his victory did not satisfy the deeper hunger. Disenchantment remains—not because of electoral failure but because of symbolic insufficiency. The personality that rose from the ashes did not transcend the ruins; it reflected them. However, the notion that no outcome ever suffices does not imply that the Right has failed; instead, it reveals that settling for less remains unacceptable to those within the movement who still strive for what is best—morally, pragmatically, faithfully, and intellectually. While some may be content with a leader whose image mirrors their own, whose rhetoric aligns with their resentments, or whose appeal is rooted more in performance than substance, many still long for something more enduring. Not perfection, grandeur, spectacle, but goodness. The fact that such a figure has yet to emerge—or if he has, has not been overwhelmingly preferred—signals the future of America.

The greater concern lies not with the present longing but with the coming generations, who may no longer possess a sense of what is good, righteous, and worthy of the People's vote. As the symbolic stage of the nation continues to erode, America would do well to observe not only whom the youth choose to follow but also what qualities they come to admire in a leader if they continue to engage in the electoral process at all.

The last election made plain the abundance of support for a near-communistic usurpation of the country. Although halted momentarily, it still brews on the not-so-underbelly of America's political and cultural terrain. If the ‘new’ Right, or what is to come of it and as it is called for now, wishes to vanquish the serpentine, Machiavellian immoralists poised to re-enter the chamber, then it must first turn inward. It would do well to examine the rot within its walls—the roaches nesting in its own cabinets—before claiming the moral ground it seeks to defend.

Perhaps the spell of nigredo is yet to come. Possibly, the party must fall again to understand where to step. In the individual, such a transformation is natural when facing himself and reshaping his outlook on life, which was previously unrevealed to him, before Ephinany seized him and God unveiled the possibility of what could be, given that he confronted himself, unburying all of his aspects, both positive and negative, into the light. There, he is most vulnerable yet unafraid.

“Assimilation of the shadow gives a man body, so to speak; the animal sphere of instinct, as well as the primitive or archaic psyche, emerge into the zone of consciousness and can no longer be repressed by fictions and illusions. In this way, man becomes for himself the difficult problem he really is. He must always remain conscious of the fact that he is such a problem if he wants to develop at all.”

(Jung, The Psychology of the Transference, CW 16, ¶452).

Great piece. I’ve never studied Jung, but as you were describing the concept of transcendent meaning giving a rootedness to action, I couldn’t help but think of two post-its I have on my desk. One sums up the governing principle I leaned into as I wrote my first novel. The other lists my marching orders for the second. Both are part of a Fantasy-Western series which might be broadly described as a re-enchantment effort. Really appreciated this read. Thanks.

“Stay True - Story, Character, Voice”

“Instinct, Movement, Home”