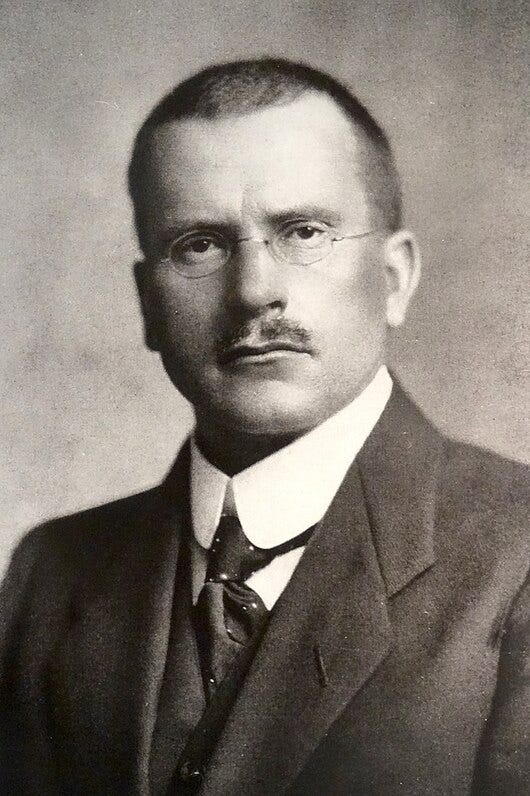

The Reclusive Pioneer of Psychology

Rarely is Carl Jung mentioned in prominent psychology/philosophy spaces or dwellings. Why is this?

The main reason is quite simple:

Jung detested popularity. This is evident in his philosophy, essays, and precise analysis of how the collective manipulates individuals in mysterious, borderline devious ways. Not only did his preference determine the path of his contributions, but his complex and often controversial ideas resisted easy categorization.

His theories on the collective unconscious, individuation, and archetypes were groundbreaking, enlightening a path of the psyche that psychologists had not delved into as extensively; however, as mentioned, those theories came with their share of criticism and controversy.

As a result, Jung's work—like Friedrich Nietzsche's—became practically tarred and feathered in one way or another. Jung, aware of his standing in psychology and the impact of his ideas, was wary of the potential for his work to be misapplied or turned into a dogmatic system.

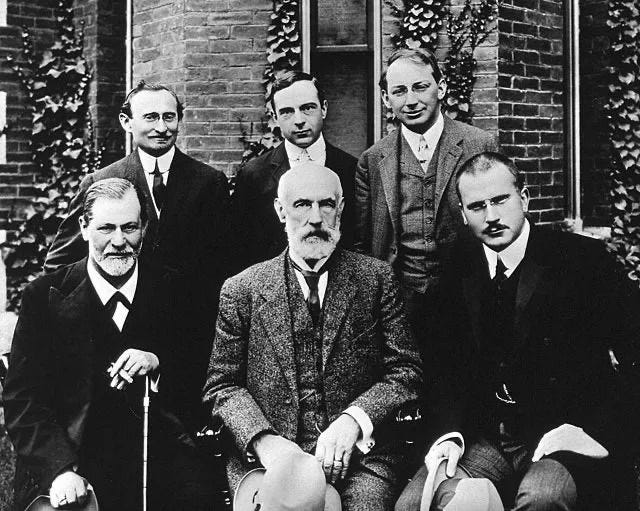

As a European—and one living in the most turbulent time in world history—Jung observed America's lightning-speed acceleration and the state of psychology in the West. However, he did not do so in a discriminating or pessimistic tone, contrary to the works of Spengler or Jünger.

As a side note, understanding the reality that enveloped Jung in the early 20th century is essential. He witnessed the unfolding of the "blond beast"—a metaphor penned by Nietzsche, reflecting the primal ferocity stirring within Europe's socio-political landscape. Jung's essays from the 1930s onwards display his ideas as he delved into the collective psyche's engrossment that gripped entire nations during this tumultuous era.

Nevertheless, Jung's unique perspective allowed him to make an understandable judgment. He noted that Western psychologists—often misunderstanding his analyses—approached psychology with a materialistic, almost scientific rigidity, a trend he critiqued for neglecting the depths of the subjective and unconscious realms of human experience.

Jung traveled the world, trying his own theory on the comprehension of Western academics and psychologists. He spoke with people of all kinds, from indigenous communities in Africa to Native American tribes in New Mexico, while engaging with the intellectual and academic circles of major cities in the United States. Such trips tended to reveal to him facts about himself and the European psychology he knew best.

During his travels, Jung developed a deep respect for the cultures he encountered, particularly their use of symbols and rituals. He did not depreciate those he met; instead, he recognized that the symbols and customs of each culture were expressions of the collective unconscious. For Jung, analyzing a culture was essential, as it is rooted in the collective unconscious—the underlying essence of the people themselves—that manifests dramatically during the downfall of nations. He had a unique ability to articulate the connection between the identity of a people and the broader influence of its nature on the world stage.

Jung remained individualistic throughout his life, reflecting the mindset of his European heritage. It often seemed to fare better psychologically than the unruly, rebellious, and hormonal American in its youth.

As for desecrating graves, it is always Nietzsche who bears the brunt of this act. After Friedrich Nietzsche’s death, his sister, Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche, manipulated his unpublished writings and aligned them with her nationalist views, further complicating his legacy. This manipulation contributed to the association of Nietzsche's philosophy with fascist and Nazi ideologies, although he opposed such views. Furthermore, his writing was aphoristic, dense, and easy to misinterpret, often conflicting understandings of his philosophy.

If Nietzsche's work was challenging to read while he was alive, it is undoubtedly difficult to read today. Many armchair academics seem to have clasped onto Nietzscheanism as if it were the Aryan Holy Grail.

Indeed, both men have faced their share of posthumous disrespect. Yet, with an unbiased approach—free from the influence of polished academia and social or literary groups—their contributions can be accurately interpreted and valued on their own merits.